A Prophet in his Own Town

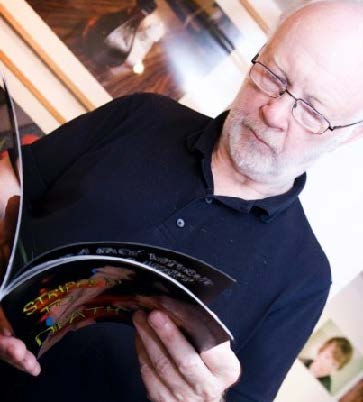

A Conversation with Barrie Todd

As part of a new series Dr Andrew Molloy chats to leading figures in Northern Irish architecture about their careers and influences. In this issue he talks to Barrie Todd MBE, founder of TODD Architects

Todd Architects have been described as “the largest homegrown architectural practice in Northern Ireland.” 1 Their steady rise in the AJ100 over the past 20 years along with the

recent opening of a new Manchester office to supplement their established Belfast, London and Dublin offices is indicative of the practice as a local and national success story.

The office was established by Barrie Todd in Belfast in 1976 during what was a particularly dark period in the history of the city. Despite the Troubles, the practice was able to establish a thriving London office within 10 years of opening, all at a time when being Northern Irish was synonymous with social unrest.

This success during troubled times raises obvious questions which were running through my head as I parked up outside Barrie Todd’s restrained and elegant self-designed house on the outskirts of Hillsborough. I had met Barrie previously when I interviewed him for my doctorate, so knew him to be affable and easy going, something that belies his achievements and standing within the profession. After a brief discussion of the problematic parking caused by the revamped nearby Hillsborough Forrest Park, we both settled at the kitchen table and set about exploring the developmental milestones of Barrie Todd as an individual, as an architect, and as the name behind one of Belfast’s bestknown architectural brands. I began by asking what led him to study architecture.

“It was my father. I wanted to study art in Belfast Tech. My father was a very good fine artist, and he told me I wasn’t good enough at art to make a living. He agreed to let me take the entrance exam for art if I did the same for architecture, and I passed both. My father was a very quiet man, a very gentle man, but he said, ‘You are not doing art!’ So, I started off studying architecture in the college of art in Durham Street in 1963. I have to say that I didn’t excel at school, but as soon as I got into architecture I saw a purpose in learning. I’m ever grateful to my father for insisting on it.” Graduating in 1969 and resisting his parent’s insistence on acquiring a secure position in the civil service, Barrie went to work with the Northern Ireland Housing Trust, the forerunner of the Northern Ireland Housing Executive. Finding his progress into the profession frustrated by a lack of practical experience, he decided to leave and find a position in a commercial office, joining Shanks and Leighton; the practice that would go on to become Kennedy FitzGerald.

“I was working on the Model School, Enniskillen (opened in 1974 and demolished c.2009).

It was a fantastic design; Joe (FitzGerald) came up with the concept. It did away with corridors and used the central area as a multifunctional space, really ahead of its time. I got good experience there but was very unsettled. I blame it on the sixties and my youth. I was a bad timekeeper and Joe lost it with me one day in front of everybody. I said, “Stuff your job!” and literally packed my things and walked out.” Having gained his Part 3 in Shanks Leighton, the young and restless Barrie got a position in the now defunct office of Ferguson and McIlveen where he had a similarly frustrating experience as that in the Housing Trust, being stuck on door schedules for Wallace High School.

The dissatisfaction and unease that appears to have defined his first five years in the profession led to a chain of events that would result in the establishment of Barrie Todd Architects in 1976.

“A peer of mine had got himself a job in Dublin in the offices of Delany MacVeigh and Pike; (since renamed O’Mahony Pike). He was let loose on Limerick Sports Centre, and I would travel down at weekends; we designed it together. I never asked for money, it was just like the old university days. Owen MacVeigh and Jim Pike approached me to see if I would be interested in starting a Belfast office. “I left Ferguson McIlveen, set up this office for Delany MacVeigh and Pike in University Street and started to get work in, initially by word of mouth. The first big job was from Roy Mulholland, a guy I went to Belfast High School with.

He was working for a Dundalk company that made sea containers and decided he could do the same. He built this enormous container manufacturing factory in the Carnbane Industrial estate in Newry, and I was the architect. “Mulholland took a lot of the staff from Dundalk and I got to know these guys. Out of that I started doing work around Dundalk for a developer called Phil Monaghan; very small stuff, but it was helping to build the practice. Things started to do very well for Delany MacVeigh and Pike, but we had a dispute over wages that meant I decided to go out on my own. Without being persuaded Phil Monaghan, Roy Mulholland and several other big clients followed me. Delany MacVeigh and Pike had to close in Belfast because it was still in the period of Catholic discrimination and, quite frankly, there was no way a Dubliner was going to get work in Northern Ireland at the time.”

An office was established in Botanic Avenue in 1976 and it wasn’t long before the practice was given its first major commission from Phil Monaghan; Stokes House on College Square East. Being ‘given’ the commission is, in this case, a slight misnomer, as this project was earned by a moment of persistence that could have easily backfired.

“I couldn’t get any fees out of Phil, so I decided to go down to Dundalk and confront him.

I waited the whole morning in reception knowing that he couldn’t get out past me. When I was still there come lunchtime he agreed to see me. ‘You’re a tenacious boy!’ he said. ‘I’m not,’ I replied. ‘I’m starving, I can’t afford to eat!’ He paid me the cheque there and then.

“Not long after he rang me and said ‘Barrie, I admire your tenacity. I have just bought The Mayfair Cinema and Kensington Hotel on College Square East. I want to build a 30,000 square foot office and I would like you to be my architect.’ I reckon I wouldn’t have got that job if I had folded on the fees. This was 1979 and there was a paucity of work at that time due to the Troubles. That was a very big job.” Despite proving himself to the developer, there were further tests to come. The project’s client – Dublin based accountancy firm Stokes, Kennedy, Crowley (since rebranded as KPMG) – were uneasy with the apparent inexperience of the young architect. As such the CEO insisted that Barrie spent a week with established Dublin architects Scott Tallon Walker; being scrutinised, tested and cross-examined to prove his design capabilities.

“We had already gone in for planning, so I had in a sense to defend the designs. It came to the end of the week and Ronnie Tallon said, ‘Barrie is the man for the job.’ People think you get handed these commissions, but I had to work for that one.” 2

Despite winning this major commission so early on, the Troubles meant that it did not spin off into additional work as expected. Commissions remained thin on the ground for the practice whose bread-and-butter became Housing Association work and bomb-damage repairs. The final straw was the chaos caused by the Anglo-Irish Agreement, signed in November 1985 in Hillsborough Castle. Barrie and his wife Trish – an interior designer who also worked in the practice – were living in Hillsborough by this time, and a large protest demonstration was held in the village on the 15th May 1986. This led to yet another risky decision that would eventually pay off for the practice.

“The night Paisley marched his army through the village – chanting, beating Lambeg drums and all this – I decided to go to London to get some decent work. Part of the problem when I started up was that a lot of commissions were emanating from government departments and the chief architects had peers in government. There was no procurement process, so they were handing work out to people they knew. That generation of architects were creaming it and I couldn’t break in.

“I pulled together a brochure and set off. I hadn’t planned anything and the first morning I woke up and realised I had no appointments and no idea what to do. A banker friend advised that the best way best way to get to developers is through their bank managers. He was able to refer me to a few key individuals and gave me a few numbers to call.

“Over the following days, I was in Luton, Crawley, Henley – all over London – meeting developers. At the end of the week I had what turned out to be two very plum commissions. One was the conversion of 100,000 square foot light industrial buildings into offices in Clerkenwell, and the second was 100 houses in Wandsworth. I remember ringing Trish from Heathrow airport and saying, “I’m not getting the plane home, I can fly myself!” I was so elated.

“Once I’d established an office in London the word got back like wildfire that Barrie Todd was working on big jobs across the water. Then suddenly people like Brian Sloan, (chief architect in the Department of the Environment) and Mack Craig (head of the Industrial Development Board) started to give me commissions. I’m not saying they underestimated me; they didn’t know me. They didn’t want to risk giving work to a perceived unknown. It just shows you; you can’t be a prophet in your own town.”

Shortly after establishing an office in London, Barrie made the decision to move out of the two terrace houses the practice occupied on University Street in south Belfast and move into the run down ‘Northside’ quarter of the city.

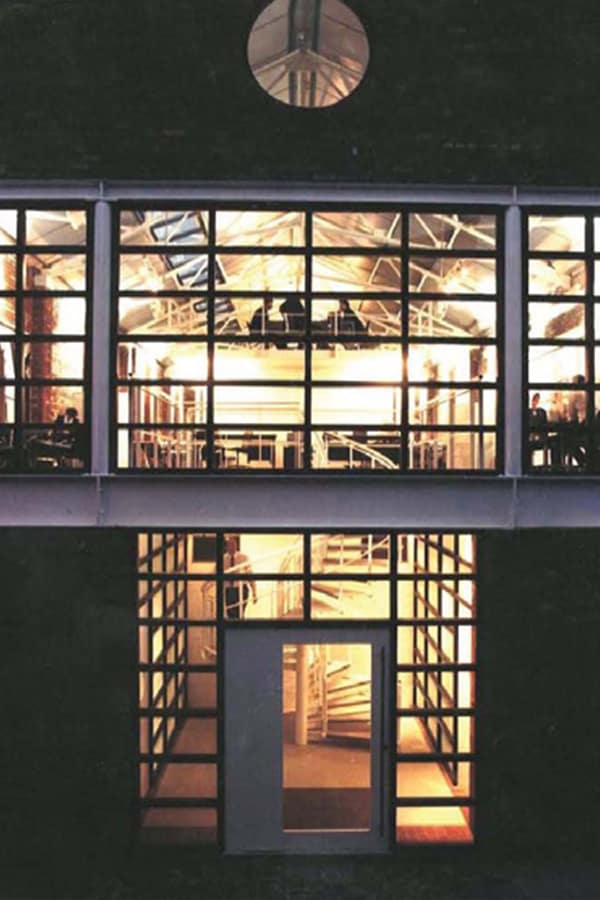

“All these architects were based in the leafy University area, and I thought we should really be in the city centre. The ring of steel had killed Belfast and the city centre really needed commercial activity. At the corner of Gordon Street and Hill Street there was this really run down warehouse which was up for rent for £1 a square foot for storage. I had a look, and it was full of pigeons and all sorts of things. Also, there was an annex to it that really was superfluous to our requirements. We approached the agents MacFarlane and Smyth – who turned out to be the owners as well – and enquired about how much it would be to purchase the building.

The guy nearly fell of his chair and said “I don’t know…eighty thousand? Do you really want to buy it?!” We had no money, but said “Yeah, we’ll buy it!”

“We went for planning for an architect’s studio, with a restaurant and an apartment in the annex. The reaction from most people was “A restaurant and an apartment…down there!?” Shortly after submitting planning I got a call from Nick Price, one of the many restaurateurs who had to get out of the city during the Troubles. He had heard I was building a restaurant on Hill Street, and he made me an offer. We shook hands then and there.”

During the late 1980s, the worst days of the Troubles appeared to be in the past and the process of reinvigorating the city centre was underway. Sir Richard Needham, the Under- Secretary of State of Northern Ireland from 1985 to 1992, led the charge in the inner north of the city. The construction of CastleCourt was a key component of this redevelopment, and it is thanks to Needham that the proposed pastiche Victorian facades to Royal Avenues were changed to the Rogersinspired glass and chrome monolith we have now.

While the benefits of CastleCourt have been debated – with criticisms levelled not only at the style of the building but the impact it had on the urban grain – Needham also introduced an urban development grant of 75% for all costs to owner occupiers of new developments in the city, something which Barrie Todd Architects availed of in the construction of their new Hill Street Offices. As such, Needham kept an eye on this small scale but potentially transformative intervention taking place close to his more ostentatious urban scheme

“Before the building was occupied, Needham would send senior civil servants to see how we were getting on. We invited him to officially open the building. Nick’s Warehouse was open by that stage, so Nick did the catering. We sat up in the mezzanine with Needham, the heads of planning and the road service, and other senior civil servants. ‘Wonderful job Barrie,’ he said,

‘I do hope they are going to keep the cobbles.’ I informed him Road Service had decided they would not because they were frightened of people lifting them to throw at the police.”

At this suggestion Needham intervened and provided money to complete the streetscape, with works being completed by the Paul Hogarth company. Needham’s ‘cobbles’ were retained. Northside went on to flourish and continues to do so today under the name of the Cathedral Quarter. A new section of the city activated by a single small-scale mixed-use development. One cannot help but think that the potential lessons to be learned by this project have been missed.

The early nineties saw a change in fortunes for Barrie Todd architects, this time for the worse. The building-boom of the late 1980s led to an inevitable economic crash. The practice had grown to around 100 employees by this stage, evenly split between Belfast and London. As developers went bust and defaulted on fees, the London office ended up losing in the region of £300,000 in one year, and with that all but two London staff were made redundant.

“Belfast was a bit of a roller-coaster as well. When you’re building up a practice there’s a lack of continuity; highs and lows which inevitably lead to redundancies, which is a very difficult thing. I decided not to give up in London. For a start we were still servicing jobs that were on site. Then we had another stroke of luck, we got three big commissions in virtually a year, two here and one in London.”

One of these projects was the development of a masterplan for Kingston Upon Thames University, which went on to win a Civic Trust Award in the year 2000. This was just over a decade after the Hill Street office had done the same. At the same time, the practice won the commission to design the new Children’s Hospital at the Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast.

“The Children’s Hospital was a big change for us. We were simply asked to make a presentation, and then we were added to the select list for the competition. The brief asked for the building to be of domestic scale so as not to frighten children but be of a design that would give reassurance to parents. I always remember one of my eldest boy’s first birthday parties having all his mates round. They went berserk, so we let them out and they were all over the place.

I came to realise that children don’t like domestic spaces, they like to be out and in the street.

“The street as the centre of the children’s hospital became our big selling point, in so far that it would make children feel relaxed because they liked open spaces. At the same time, it would reassure parents because it was also a bit authoritarian; almost like a church. Our design broke all the rules and I have to say it wouldn’t have happened if it hadn’t had been for John Cole, executive of Health Estates and an architect. It still looks well.”

The building was awarded the Liam McCormick Prize in 2000. At the same time, at what must have been a high point in the architect’s career, thoughts were turning to what was best for the future of the practice. “As I approached retirement age I convened a meeting with the senior architects in the practice.

I told them that those who exercised the Three ‘G’s of Architecture – ‘Getting Work In,’ ‘Getting Work Done’ and ‘Getting Money In’ – would have an opportunity of becoming directors in Todd Architects. Paul Crowe and Peter Minnis immediately began to work on those requirements.

“In the meantime, the post ceasefire attraction saw several developers and architectural practices showing an interest in Northern Ireland. One such firm from Edinburgh called Percy Johnston Marshall approached me with a view of purchasing the practice. Extensive negotiations ensued involving lawyers and accountants over a period of a year. As this process gradually proceeded I became more and more uncertain, not about the agreed purchase price but how PJM would treat Peter and Paul both of whom had been very honourable to me.

That reluctance was perceived by Bruce Haire, PJM’s negotiating principal.

“On the day of Todd’s office Christmas party, Mr Haire flew especially over to Belfast to try and persuade me to complete the deal. I clearly remember saying: “Bruce, I have never looked at this amount of money and said no…” He left in a rage! That evening at the Christmas party I was coincidentally seated beside Peter and Paul who were naturally inquisitive about my meeting with Bruce Haire earlier that day. When I informed them that the deal with PJM was off, they immediately lit up and announced that they had raised the same amount of purchase money. And as they say, the rest history.

“While I was retained until 2005 to ease the transition, Peter and Paul very quickly took over all aspects of running a practice and ultimately took it to a completely different level which exists to this day.”

During this transitional period Barrie was incredibly busy, involving himself with aspects of local architecture above and beyond Todd Architects. He served as President of the RSUA from 2000 to 2002, and during this time Barrie formulated the concept behind both PLACE, the Built Environment Centre for Northern Ireland which opened in 2004. Shortly after this, from 2007 to 2010, he acted as the inaugural chair of the Ministerial Advisory Group, better known as MAG.

“There was a lack of understanding between the public, the educated public and architecture, and I thought the way to address this was to have an Architecture Centre, that would come to be known as PLACE, where the public could participate and eventually become influential. There was no point in putting it up in leafy suburbia or the RSUA; it had to be in the main shopping street. We looked at several opportunities, one which was an abandoned underpass in Oxford Street, but the Road Service wouldn’t allow it. We eventually persuaded Belfast City Council to let us have a place in Fountain Street, and we got free rent, rates and utility charges. PLACE is gone now, and the irony is that the Arts Council have an architectural policy, and they pulled the plug in 2019.

Then, in 2007, Trevor Leaker was president of the RSUA and he asked me if I would be the first chair of MAG. My immediate response was, “I’m honoured.” I worked on the basis that MAG was there to monitor and ensure delivery of the Architecture and Built Environment Policy, which was written by DCAL, and in my opinion is one of the best Architecture policies I have read; it is more prescriptive than aspirational, and therein lies its strength and weakness. In my two-year term we talked to departments that had never even heard of it or just didn’t want to know. We selected sections of the policy to try and get movement on it, and nothing happened.

“So, at the end of two years they asked me if I would stay on for another term and I declined; it wasn’t working. My experience with MAG illustrates the difficulty in getting the civil service to apply the Built Environment policy, it was hopeless.”

In 2010, Barrie lost his daughter Jill to cancer at the age of 23. She received a degree in photography from Edinburgh Napier in 2009 and had a promising career ahead of her. Jill’s colleagues, friends and family established the Jill Todd Trust in her memory with the objective of raising funds for cancer research, promoting of the art of photography and the promotion of early careers in photography. This also led to

Barrie establishing ‘Ask an Architect.’

“We spoke to a friend who was a fundraiser and he suggested using the profession by getting architects to give consultations in return for charitable donations; we thought it was a very good idea. For the first couple of years it was run by PLACE and me. Eventually we involved the RSUA to give it credibility for the consultees. It was hard work to get the publicity and that sort of thing, so the RSUA gradually took it over, in a very kind way.

“It’s been going for six years and we’ve raised £60,000. The benefits are tripartite; the client gets a very inexpensive consultation; the architect gets a chance to meet new clients, and the charity gets the money. People think twice on knocking on architect’s door for fear of being charged too much, so it opens the profession up to people who would not otherwise engage an architect. It connects to my aspirations for what PLACE should have been doing.”

Barrie’s self-described ‘swan song’ project with Todd Architects was ‘The Boat,’ an iconic mixed-use development situated on the corner of Queen’s Square and Donegal Quay. Despite officially retiring in 2005 Barrie continued his involvement throughout final stages of construction until the building’s completion in mid-2010 on the request of the developer.

On leading a tour of the building for the Open House Festival in 2018, Barrie discovered that the building had been named as the ‘Mixed-Use Building of The Year’ at the prestigious LEAF Architecture Awards, an event he had missed due to the sudden death of his daughter some months before. The Judging panel included high-profile international architects including Richard Rogers, Zaha Hadid and Norman Foster, with Zaha Hadid singling the building out for glowing praise during the awards ceremony. Despite finding this out some seven years after the event, Barrie recounts this story with obvious pride and a sense of satisfaction that he had retired at the top of his game.

As our near three-hour conversation drew to a close, I was struck by how much we didn’t talk about. His 2008 MBE for services to architecture, the work he did beyond the construction of the Hill Street office to encourage the redevelopment of the Cathedral Quarter, the part he played in the construction of the MAC, what the Jill Todd Trust has achieved for young photographers. Also, how little we talked about specific buildings, drilling down into the creative process or highlighting specific projects for their technical, creative or urban challenges or achievements. What did emerge, however, was the fascinating narrative of the development of a young and restless architect into a fully formed and confident designer, business owner and practice runner who was both commercially successful and creatively fecund throughout his career. It is a story replete with luck – both good and bad – balanced by a large amount of bloody minded persistence, underpinned by calculated risk-taking and intelligent business decisions, all while weathering the frustrating sectarianism of local politics and the fickle fortunes of boom-and-bust national politics. Barrie Todd has been through it and survived, and remains remarkably matter of fact and humble about it all.

Dr Andrew Molloy

1 Belfast Telegraph. ‘Belfast Telegraph Business Awards: Todd Architects Joint Winner for Best Established Small/Medium Business’. Accessed 19 April 2022.

2 Stokes House has been recently redeveloped by RMI Architects as ‘The Kelvin.’ For more on the background to the building of Stokes House and subsequent redevelopment refer to Perspective, April 2021

close

close